Redstarts I. – Hybrid redstart from Slavíč, Czech Republic

6

This is an English translation of an original Czech article that was published in July, 2021.

The second part of a miniseries about redstarts can be found here: Redstarts II. – Redstarts in puberty and on other bird teenagers.

On 19th April 2020 an interesting male redstart was observed for the first time in Slavíč, a part of Hranice na Moravě in the Czech Republic (its observation in AVIF – Czech ornithological faunistic database). So our redstart specialist, Filip Petřík, went there to take a look at this individual to try to learn more about him. It seemed that this individual might be of hybrid origin, but the story is far from simple!

The truth is, the situation with redstarts is far from simple in general. Before we will talk about our interesting bird, let’s make a short detour.

We, in central Europe, are used to two species of redstarts and the fact that, at least the males, are easily separated on plumage alone[1]. Almost the whole Europe is inhabited by just one subspecies of the Common Redstart (Phoenicurus phoenicurus phoenicurus) and one[2] subspecies of the Black Redstart (Phoenicurus ochruros gibraltariensis).

Redstarts as we know them – European subspecies. Left: male of the European Black Redstart (P. ochruros gibraltariensis; CZEP21-064), right: male of European Common Redstart (P. p. phoenicurus; CZEP20-144). Both males are "old", i.e. in their second year of life or older.

If we leave our imaginary house, we might learn that the world out there is full of quite different redstarts and some of them does not even look like they belong to the same species. We don't need to go very far, actually – in Turkey we will encounter interestingly coloured subspecies of both "our" Redstart species. The European subspecies of Common Redstart is replaced by "Caucasian" Common Redstart (P. p. samamisicus) that has a white wing panel, almost same looking like in the Black Redstart we know. But the Black Redstart itself is even more interesting. In Turkey lives a very interesting subspecies of Black Redstart – P. o. ochruros, which is quite variable in colour but generally has an orange belly like Common Redstart. The more to the east we go, the more the black redstarts look like the common redstart, until we finally get to Central Asia where there lives another subspecies of Black Redstart which has its similarity to Common Redstart encoded in its latin name – P. o. phoenicuroides. This subspecies basically looks like Common Redstart apart from black on throat reaching the upper breast and white forehead is either absent or not as pronounced as in Common Redstart. Otherwise, the similarity is striking.

And why am I telling you all this information? Because it’s there, in Central Asia, where the interesting story begins. The genus redstart, or better to say Phoenicurus, actually originated roughly 6 million years ago somewhere in Central Asia and the Himalayan mountain range[3]. Repeatedly because its advancement was hastened several times by onset of ice ages[4] and drier periods, only to spread again after the retreat of ice sheets. And it was during this unfavourable periods of redstarts populations being separated, when redstarts evolved into separate species – including Common and Black Redstarts. These are, actually, two quite closely related species which separated one from each other roughly 3 million years ago. During this period, they spread to their present distributions with aforementioned breaks during ice ages or dry periods. These periods probably separated some populations of these two species for a while so some genetic differences accumulated in their genomes and we can quite easily track them these days. This fragmentation probably also led not only to genetic differences, but also to evolution of distinctly coloured morphs or subspecies in the Black Redstart. We can only speculate that the way black redstarts look at the eastern part of their distribution is the "original" look of this species from the time it separated from Common Redstart and that the black and grey look we know from Europe is a derived one. No genetic study investigated it yet, but it looks quite plausible (to me)[5]. It is noteworthy that Common Redstart is also genetically differentiated but it is not reflected in its appearance. Both subspecies of Common Redstart are quite similar in appearance, but there are also huge genetic differences "inside" each subspecies, and therefore among uniformly looking individuals.

At least in the European part of its distribution, a preference for different breeding habitats evolved in these two species (otherwise it would be difficult for them to coexist). Black Redstart used to be a species inhabiting rocky areas without trees, very often mountains above the tree line and Common Redstart preferred open woodlands and its margins. It all changed when both species moved to the close proximity of humans – to villages and towns. That also led to the spread of Black Redstart northward in Europe, where it was not present in the past. And even though both species prefer a slightly different habitats in human settlements (the difference is mainly in the number of trees), it is still a very fine mosaic of different habitats. That lead to a situation that did not happen in nature very often before: both species came into close contact. As a consequence, quite a novel phenomenon emerged – interspecific hybridization[6]. There are many very interesting details about this example of hybridization. But for this article I am going to point out especially the fact that hybrid males produced by this forbidden love look almost exactly like Black Redstarts from the subspecies phoenicuroides. I.e. those from the east of Black Redstart distribution and from the area where both our species of redstarts probably originated. Not only it is truly interesting from the evolutionary point of view but it also complicates a bit the identification of such individuals as true hybrids. Because similarly to some exotic New World warblers or Asian species of leaf-warblers that may wander far from its normal distributional range and end up in Europe, some of the members of our "ordinary" species of birds can become vagrants and wander far away from their distant population they call home, too. And the Black Redstart of the subspecies phoenicuroides is no exception.

But let us get back to our redstart from Slavíč. That individual looked exactly like a hybrid of Black and Common Redstart. Or like an individual of P. o. phoenicuroides from far east. Filip was able to trap the bird, ring it, thoroughly measure it and take some very nice pictures (his observation in AVIF ). He consulted this redstart with Vincent van der Spek, probably the best expert on hybrid and "eastern" redstarts. His verdict was clear – it is a hybrid. I, personally, was not happy with such a verdict made "from a desk", even though it was done by the best expert. I contacted Filip and we agreed that we will try to find out if it is a hybrid or not using a genetic analysis. Filip foresightfully collected few small feathers from the redstart. Indeed, we were able to successfully isolate sufficient DNA and… and the outcome is a hybrid redstart (as you already know from the title). Well, experts are experts for a reason, right?

I, personally, was also very interested to see this animal, and if possible, take some pictures to my gallery. Not only because it is a quite unique animal by itself, but since we performed the genetic analysis, it would be a nice addition to the gallery thanks to its story[7]. I asked Filip, in case that this redstart will survive to the next year, to join him and take some pictures of it. Everything went well and the next year we went to see this individual again with the aim to trap it once more. The purpose was not just some "hunting whim", but we wanted to document in great detail how such individual changes in appearance throughout its life which is something that is unknown and it is also very interesting regarding the well-known change of appearance which males of Black Redstarts are undergoing throughout their lives (which is also a very interesting topic that I tried to summarize in another article: in this one ). To our surprise, the redstart looked almost the same as the year before which raised more questions than it answered.

We thought that the redstart in 2020 was an individual in its first year of life, but comparing the photos Filip took in 2020 with those taken in 2021 kind of ruined this hypothesis. Males of Black Redstarts usually look like females during their first year of life and their full male breeding plumage is being developed during their second year of life (see the article linked above). That raised a question if the hybrid also looked like a female during its first year of life and as a consequence escaped our attention until 2020 when it acquired conspicuous plumage and was noticed for the first time. After the close inspection of its plumage, we are unable to tell if that is true or not. Common Redstarts, on the other hand, do not undergo such a dramatic change of appearance during their lives, but considering the song of this hybrid individual, its habitat (both resembling more Black Redstart) and its mate (Black Redstart) with which it reproduced at least three times, it is possible that this hybrid might resemble Black Redstart also in other characteristics.

Right after the capture, I was struck by the appearance of the animal. Much more subtle than Black Redstart, more like a Common Redstart but noticeably bigger. Definitely an extraordinary individual. See for yourself:

Photos of hybrid redstart from Slavíč taken in May 2020 by Filip Petřík and Ondřej Boháč during the first trapping of this individual. In that time the individual looked like a bird in its first year of life (2CY, euring: 5). Photos courtesy of Filip Petřík and Ondřej Boháč.

Photos that I took during the second trapping of the same hybrid individual in May 2021. The individual is definitely at least in its second year of life (therefore 2CY+, euring: 6), but it looks almost the same as in previous year including the appearance of greater coverts or tail feathers. This raises question how old it was the year before? Who knows? You can find this individual here in the gallery: CZEP21-170

One of the criterion used for identification of hybrid redstarts is the so called wing formula. That is a species specific trait, very often used by ringers, telling us the proportions of lengths of each primary flight feathers and which of them then form the wing point. Wing formula also contains information about the number of primaries that are emarginated (thinning of outer vane). Wing shape (and therefore wing formula) is to a great extent dictated by the distance certain species migrates and if there are two closely related species differing in their migration strategy, then the one which migrates further from its breeding grounds, has usually more pointed wing (wing point is formed by less primaries) with fewer emarginations. That is the case also in our two species of redstarts. Hybrid individuals then tend to have their wing formula somewhat in between of those of parental species.

Hybrid redstarts are apparently becoming more and more frequent part of our ornithofauna. Redstart from Slavíč is not the only, not even the first such case in Czech Republic. It is worth to pay close attention when watching redstarts and even more so, if you see a weird individual. These are traits typically associated with hybrid redstarts:

At the same time, also pay close attention to any breeding attempt of Black and Common Redstarts. Hybrid individuals do not arise de novo, of course. Ideally, try to document all such cases or you can contact Filip Petřík for advice (filepetrik@seznam.cz).

Not all individuals looking like hybrids are necessarily hybrids, though. Vagrancy of eastern Black Redstarts, which strikingly resemble hybrid individuals, are not entirely uncommon. Unlike hybrids which are typically found during the breeding season, vagrant redstarts appear most commonly during autumn migration or overwinter in Europe. Telling these two apart only by visual clues requires seeing the bird very well or very detailed photographical evidence. If you come across such individuals during your ringing activities, you can use our genetical services and identify such individual molecularly (see UBOGEN , unfortunatelly still only in Czech). You can find few outstanding papers dealing with ID of such individuals in great detail in references below.

Following text is meant (not only) for those who would like to know, how did we identified this individual as hybrid using genetical analyses. It is not possible to go into great detail in this post so I will assume that the reader has at least basic knowledge of genetics and molecular analysis, but I will try to use as few technical terms as possible.

Identification of hybrids, in most cases, is not especially easy discipline. Especially when the parental species are very similar and you cannot identify the hybrid on its appearance alone. Then, you have to use some sort of genetical analysis. That tend to be far more difficult than e.g. (sub)species identification using a mitochondrial marker that is nowadays quite regularly done. In this case, you have to find some region in the nuclear genome of presumed hybrid that will be different in both parental species and then sequence it. You have to choose nuclear genome, and not the mitochondrial one, because of there are two copies of each chromosome in nucleus, one inherited from mother and the other one from father. The sequencing of nuclear genome is much more difficult than much more common sequencing of mitochondrial genome (of which there is just one copy in each individual), because, simply put, you have to take apart the two chromosomes and read them independently. Another complication is the fact that the public databases are not especially rich in this kind of information so we would have to have our own reference sample from both parental species and then probably also design and test our own markers on "pure" individuals. That, of course, would make such analysis way too expensive for a random curious person.

Public databases, on the other hand, are crammed with sequences of the mitochondrial genes of plethora of species. The reason is simple, mitochondrial genes are frequently used for e.g. phylogenetic analysis and reconstructing evolutionary history of species. The advantage of mitochondrial genome is its great instability in time and therefore ability to gain mutations, and since there is only one copy present, it is easily sequenced. Disadvantage is the fact, that there is only one copy in each individual, so it is virtually useless for identification of hybrid individuals. All hybrids will also have just one copy (inherited in vast majority of cases from mother), so even hybrids have their mitogenome "pure", derived from only one species.

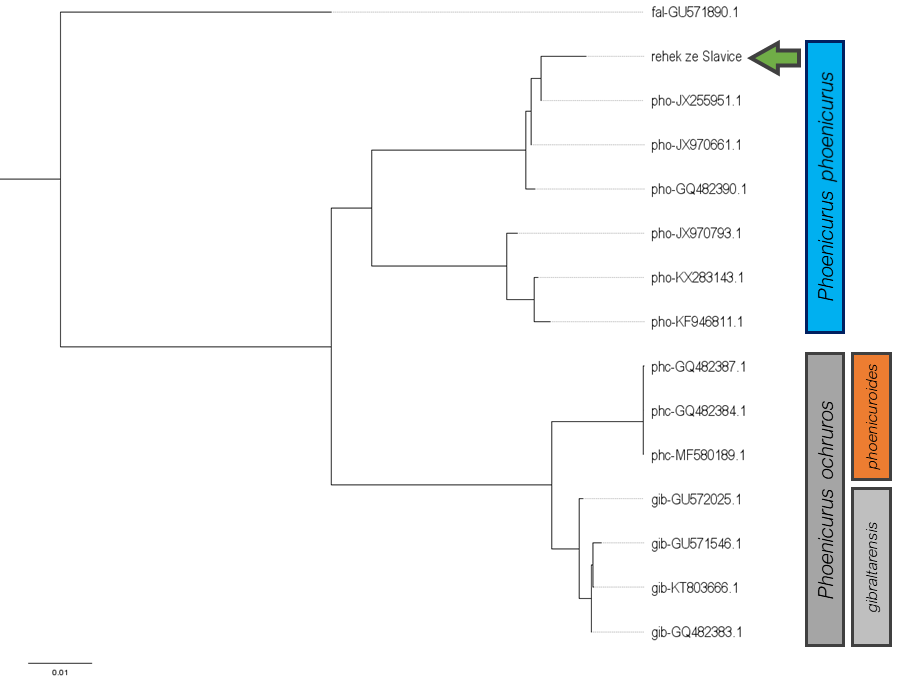

The redstart from Slavíč did not looked like an ordinary Common or Black Redstart, so we could use sequencing of its mitochondrial genome at least to identify one of the species which produced it and in case we are lucky, to tell if it is a hybrid. If the sequence obtained would belong to the Common Redstart, we would be sure that it is a hybrid whose mother was a Common Redstart. But what if we would get a sequence belonging to Black Redstart? Would it be possible to say whether it is a hybrid between Black Redstart mother and Common Redstart father, or indeed an eastern subspecies of Black Redstart? Well, in most cases probably not. But here, the history of the evolution and spread of Phoenicurus redstarts comes in play. Genetical information stored in mitochondrial genome of eastern subspecies of Black Redstart is consistently different than that of other populations, including the European one. So even with this simple sequencing of mitochondrial genome (in this case of the gene COI ), we would be able to tell apart a hybrid from an eastern Black Redstart. The sequence obtained would be one of these three possibilities:

And what was the result? We got the first option – a hybrid whose mother was a Common Redstart. Which is the more common variant of hybridization between these two species, by the way.

Even though this was not a very rare vagrant individual but a hybrid, the story which this individual told us was equally fascinating, not lowering its interestingness. Many people, and birdwatchers, view hybrids as something ugly and unnatrual, as a natural freak, but that is quite narrow-sighted. Not only hybridization played a major role in shaping evolution of many species (of geese or even human!), but it is quite unfair to the animal itself. In this case, it is not a weird outcome of a hobby of some finch breeder, but quite interesting phenomena, something one only reads about in books about evolutionary biology. And then, there is this opportunity to see it in real life. Of course, many questions remained unanswered, many new appeared, but that is the way scientific discoveries work.

How many hybrid females we miss? How do the male hybrid redstarts look like during their first year of life? And how their offspring look like? Are we even able to identify them? And how many of such redstarts there can be?

I find it fascinating.

I would like to thank Filip Petřík for his help during writing this post.

Všechny odkazy se otvírají v novém okně.

First observation of redstart on AVIF: https://birds.cz/avif/obsdetail.php?obs_id=8686830.

Filip's observation of redstart on AVIF: https://birds.cz/avif/obsdetail.php?obs_id=8825667 and ebird: https://ebird.org/checklist/S69602808.

Article of Laurens Steijn about identification of eastern Black Redstart and their separation from hybrids of Black and Common Redstarts: Steijn, L.B. (2005) Eastern Black Redstarts at Ijmuiden, Netherlands, and on Guernsey, Channel Islands, in October 2003, and their identification, distribution and taxonomy. Dutch Birding 27: 171–194 [PDF, 4.43 MB].

Articles by Vincent van der Spek and Nicolas Martinez about hybrid redsatrts and eastern Black Redstarts, their identification and their occurence in Europe:

Paper by Ondřej Sedláček et al. about the separation of urban habitats between Black and Common Redstarts: Sedláček, O., Fuchs, R. & Exnerová, A. (2004) Redstart Phoenicurus phoenicurus and black redstart P. ochruros in a mosaic urban environment: neighbours or rivals? Journal of Avian Biology 35: 336–343, doi: 10.1111/j.0908-8857.2004.03017.x (unfortunatelly without publicly available PDF).

Evolution of genus Phoenicurus, its origin, spread and speciation is described in following paper: Voelker, G., Semenov, G., Fadeev, I. V., Blick, A. & Drovetski, S. V. (2015) The biogeographic history of Phoenicurus redstarts reveals an allopatric mode of speciation and an out-of-Himalayas colonization pattern. Systematics and Biodiversity 13: 296–305, doi: 10.1080/14772000.2014.992380, [PDF, 599 kB].

Paper about genetical differences in Common Redstart mentioned in the text: Hogner, S., Laskemoen, T., Lifjeld, J.T., Porkert, J., Kleven, O., Albayrak, T., Kabasakal, B. & Johnsen, A. (2012) Deep sympatric mitochondrial divergence without reproductive isolation in the common redstart Phoenicurus phoenicurus. Ecology and Evolution 2: 2974–2988, doi: 10.1002/ece3.398, [PDF, 1.03 MB].

[1] Identification of females is a bit harder, but we will talk mostly about males in this post. It looks like a gender-biased view but biologicaly relevant view. See for yourself. [2] According to some authors there are two subspecies – populations from Iberian peninsula are a bit different (they show black back) and sometimes they are treated as separate subspecies P. o. aterrimus. [3] Like e.g. mountain finches (Leucosticte) or accentors (Prunella). [4] Beware, do not confuse with quaternary cycles of ice ages, that happened much later. [5] Try to put males of following (sub)species one next to each other: P. o. gibraltariensis, P. o. ochruros, P. o. phoenicuroides, P. phoenicurus. You will get almost continuous transition from one form into another. [6] Interspecific hybridisation most probably occured also in the past, but it seems to be noticeably more common in recent decades. [7] Which you are actually reading right now. May 2022 | Ringing

A story about redstarts of Eurasia

"Caucasian" Common Redstart (P. p. samamisicus). Author: Nik Borrow, CC BY-SA 2.0.

Subspecies of Black Redstart from Central Asia, P. o. phoenicuroides. Author: Harvinder Chandigarh, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Subspecies of Black Redstart from Central Asia, P. ochruros phoenicuroides, showing variation in the extent of white on the forehead. Author: Imran Shah, CC BY-SA 2.0.

Redstart from Slavíč

May 2020

May 2021

Wing formula

Left: Black Redstart, P. ochruros (CZEP21-064), middle: hybrid (CZEP21-170), right: Common Redstart, P. phoenicurus (CZEP21-142).

Watch out for weird redstarts

And how did we find it out, anyway?

Phylogenetical tree of sequences of two species of redstarts and their subspecies (and of a Collared Flycatcher serving as a so called outgroup), sequence of the redstart from Slavíč is marked with green arrow. The graph clearly shows that our redstart is well placed among other Common Redstarts. You can also notice the divergence into two genetical groups in Common Redstarts as was mentioned in text. Numbers behind the three-letter abbreviation link to the accession number in GenBank database .

Few words at the very end

References and further reading:

ID of hybrids and eastern redstarts: Spek, V. Van Der & Martinez, N. (2018) Identification and temporal distribution of hybrid redstarts and Eastern Black Redstart in Europe. Dutch Birding 40: 141–151 [PDF, 564 kB].

Summary of all avalable information about the occurence of 121 hybrid redstarts in Europe and north Africa: Martinez, N., Nicolai, B. & van der Spek, V. (2019) Redstart hybrids in Europe and North Africa. British Birds 112: 190–210 [PDF, 2.02 MB].