Redstarts II. – Redstarts in puberty and on other bird teenagers

20th May 2022 | Ringing

This is an English translation of an original Czech article that was published in July, 2021.

The first part of a miniseries about redstarts can be found here: Redstarts I. – Hybrid redstart from Slavíč, Czech Republic.

I got an inspiration to write down this article after too frequently repeated contributions in various facebook groups, whose authors had always one in common – their astonishment that a phenomenon called “delayed plumage maturation” exists in some bird species, in particular in Black Redstart. It seems that many people have overlooked it in the books, despite the fact that this aspect is nothing hidden, obscure or otherwise concealed. I wrote this article for those of you, who would like to learn more about this phenomenon.¨

When we look out of the window in the summer time, we might be lucky and spot a family of songbirds, more specifically the parents feeding the recently fledged offspring. These fledglings very often differ in appearance from their parents. Of course, the colour pattern is usually similar, but the specific colours are often pale, duller, or even completely different in some species (e.g. spotted fledglings of many flycatchers). On the contrary, feathers of other fledglings shine with freshness compared to their parents (e.g. in reed warblers). However, their feathers are often more messy at first glance. A closer look reveals why – the individual feathers tend to be thinner, with fewer lateral branches that hold together worse. Therefore, it is not surprising that the young very soon exchange this plumage for their first adult plumage during the first, so-called post-juvenile moult. This kind of plumage is, in most cases, difficult to distinguish from the plumage of older birds when viewed through binoculars[1]. Sometimes young birds are less brightly coloured or have a smaller range of a certain colour, but in a flock of greenfinches on a feeder in the winter, for example, you will find it difficult to distinguish the birds born in the past summer from their potential parents. For some species, it is even impossible to determine the age at all based on plumage.

This is basically the rule for the vast majority of our songbirds (and some other non-passerines). But there are a few species that look quite different in the first year of life than in the following years. These birds show so-called "delayed plumage maturation" (abbreviated DPM). This is a phenomenon that is common in many non-passerines - we know it, for example, in large species of seagulls or in raptors, but less so in songbirds or woodpeckers and other families, which is probably related to the fact that all these groups reproduce immediately in the next breeding season, i.e. in their first year of life. This is almost a rule for temperate songbirds. Another situation occurs with songbirds in the tropics, where birds generally live longer and can thus afford to start to breed later. However, what often happens with such rules, there are a few songbird exceptions, and one of them is the well-known Black Redstart.

Black Redstart

Black Redstart (Phoenicurus ochruros) is a textbook example of a songbird species with DPM. After young redstarts are born, they grow a typical juvenile plumage - such a messy and good-for-nothing, but quite similar to the female plumage. At the end of the summer, the young redstarts moult and grow their first "adult" plumage - the plumage of the first winter/first spring, if you will. And in this kind of plumage, males and females look the same at first glance. Both sexes are equally grey-brown with an orange tail. This plumage will last them to the following year until the next autumn, when the redstarts moult for the second time in their lives. And only then do the males grow their typical elegant black-grey plumage with a white patch in the wing, which safely distinguishes them from females.

The so-called delayed plumage maturation in the European Black Redstart (Phoenicurus ochruros gibraltarensis), left: female (CZEP21-169), middle: male in the first year of life in a plumage that is indistinguishable from that of the female (CZEP21-139), right: older male in fully developed typical plumage (CZEP21-064).

But males in the first year of life only look like females. In all other respects, they behave just like old males - they sing as the old males, defend territories, mate with females and take care of their offspring[2]. But it has one "but". The situation with Black Redstarts is extremely fascinating also because there is an interesting exception. The moult pattern described above does not apply to all males. Roughly 12% of males grow another kind of plumage during the first moult that could be considered a mix of male and female plumage. Sometimes such males look almost like adults, in other cases they only grow a few black feathers. These males are called the paradoxus form, while the more common ones, those who look like females, are called the cairii. form. And why do "paradoxical" redstarts look like old birds and cairii don't? Unsurprisingly, testosterone is to blame. Birds that have higher concentrations of it in their blood during moult will grow feathers in the form paradoxus. For those who have it lower, they will grow a female plumage and become the form cairii.

A typical male redstart of the paradoxus form. The fact that it is a male in its first year of life is revealed by the presence of juvenile flight-feathers and wing coverts (more below; CZEP20-136).

The question is why this phenomenon actually arose in Black Redstart. However, it is not so easy to answer. One of the explanations that suggests itself is the so-called female mimicry. Young males are disadvantaged compared to the older ones during the breeding season, for example by their unfamiliarity with local conditions (territories, food sources). Thanks to female-like appearance, they can be spared an excessive aggression from older males and find their own place in the world. Other explanations may be related to the better survival of such individuals, as they are less noticeable to predators (in dimorphic species, females are generally coloured less spectacularly or directly cryptically), or they simply use this way to indicate who is new here and who is already an experienced matador. The truth is, we don't know exactly why this is happening. However, if we look at the original habitat of the Black Redstart, i.e. the mountain forest-free area, we find out that the young redstarts (i.e. those in the first year of life) arrive at the breeding locality later than the older males and occupy lower quality territories. It is possible that the female appearance really helps them not to provoke the older males too much and thus to gain the opportunity to reproduce quietly and secretly. It is not without interest that in the urban environment these differences between territories are blurred.

Other examples

Black Redstart is not entirely alone, at least as far as Europe is concerned. The other two species of songbirds in which we encounter the same phenomenon, i.e. DPM, are, for example, the Common Rosefinch (Carpodacus erythrinus), or the Red-breasted Flycatcher (Ficedula parva). In both cases, the situation with the dependence of colour on the age of males is the same as in Redstart. The male looks like a female in the first year of life and only in the second year (i.e. after the first breeding season) does it grow the typical male plumage. In Common Rosefinches, the iconic red colouration appears (males are grey-brown like females in the first year), and in Red-breasted Flycatchers, an orange throat patch appears also only in the second year (males do not have it in the first year). For Common Rosefinches, the reason will probably be similar to that in Redstarts, the higher chance of "grabbing" a female, while the old sharks do not look - young Rosefinches have a lower reproductive success. Also the circumstances in the Red-breasted Flycatcher will probably be very similar to those in Black Redstart. In contrast with Redstarts, in these two species there are no transitional forms similar to the paradoxus form of Black Redstart described above.

Similar to Redstarts, some other European songbirds show delayed plumage maturation. In the upper row it is a Common Rosefinch (Carpodacus eryhtrinus), on the left: a female in its typical brown plumage (CZEP21-185), in the middle: a male in its first year of life who looks exactly the same as a female (CZEP19-213), on the right: an older male in red plumage which is so typical for this species (CZEP21-184).

In the bottom row are two males of Red-breasted Flycatcher (Ficedula parva). On the left there is a one-year-old male in a plumage that is indistinguishable from females (CZEP21-209); on the right: an older male showing a typical orange patch on his throat and breast and a grey head (the photo used with the kind permission from Robert Doležal, birdwatcher.cz).

A quite similar situation can be found in the Barred Warbler (Curruca nisoria). In males of this species, the iris of their eye turns to richer yellow in the course of their life, as do thicken the grey stripes on the underpart of their body. However, in this species, even females undergo a similar transformation. They also have more stripes with age and the iris gets darker colour so that the old females eventually reach a similar appearance as one-year-old males. It is possible that in this species, these selection pressures act on both sexes. After all, it would not be anything special within the bird kingdom. Outside the temperate zone, the situation is not always as straightforward as we know it - that the male is the more colourful who is competing for the opposite sex.

Example of delayed plumage maturation in the Barred Warbler (Curruca nisora), left: female (CZEP20-208), middle: male in the first year of life (CZEP21-232), right: older male (CZEP20-110).

Of course, we would find many more examples of DPM among songbirds all over the world. Several of them can be found also in the temperate zone on the North American continent, such as the American Redstart (Setophaga ruticilla), which is coincidentally also called redstart, although it is not phylogenetically closely related to European redstarts. Another example could be some species of cardinals (genus Passerina), brightly coloured counterparts of our buntings of Europe, Asia and Africa. If we searched in the tropics, we would find many more such examples. For all, let's name, for example, bowerbirds (Ptilonorhynchidae), birds-of-paradise (Paradisaeidae) or some manakins (Pipridae).

Is there more?

In biology, many seemingly sharply defined boundaries and laws begin to fall apart the closer we look at the problem and the more we try to define that boundary more clearly. Usually we find a number of transitional types or types that are difficult to classify. And it is the case also with DPM. If we look, for example, at the already mentioned first (postjuvenile) moult of temperate songbirds, we will find out that birds often do not replace all the juvenile feathers that have grown in the nest. For a number of species, only the body plumage is replaced, or eventually some coverts in the wing. Very often, birds in the first year of life keep flight feathers and tail feathers that have grown in the nest[3]. They are usually paler, have a different shape and structure (but not as much as cover feathers), although in most species we do not notice it at the first glance. But there are exceptions when these "old" feathers strike the eye.

One of such cases being, e.g. Collared Flycatcher (Ficedula albicollis) or the well-known Eurasian Blackbird (Turdus merula). While the old males of both species are charcoal black (black-and-white), in males in the first year of life we notice immediatelly the eye-catching contrast between the black cover feathers and the brown flight-feathers and coverts. To determine the age of these birds, we often only need binoculars. Due to the fact that young males of Collared Flycatchers are less involved in breeding than older males, it is possible that females also notice these traits and use them to decide whether or not to start a family with such an individual[4].

Some authors consider the differences in plumage between age categories in birds after the first partial post-juvenile moult to be also a kind of delayed plumage maturation. These differences are sometimes quite pronounced, such as in Collared Flycatchers (Ficedula albicollis; top row), on the left: a male in the first year of life - notice the juvenile flight-feathers and coverts, which are brown (CZEP21-154), on the right: an older male with jet black flight-feathers (CZEP21-140).

Exactly the same applies for the European Blackbird (Turdus merula; bottom row), on the left is a male in the first year of life with brown flight-feathers and coverts (CZEP21-201), on the right is an older male, which is all black (CZEP18-323).

While the situation in redstarts or rosefinches seems to be directly connected to breeding, the question is whether this so-called partial post-juvenile moult, i.e. a situation when young birds have preserved part of juvenile plumage, can be considered DPM in the sense of, for example, female mimicry or elevated crypsis. Especially the cases when one-year-old and older birds differ, for example, only in the number of bright tips of greater coverts can hardly be considered an example of DPM in this respect, even though some authors do so. In such cases, the pressure to save energy during energy-demanding moult and the effort to make the most of juvenile plumage, which has been growing relatively recently, come into play. While juvenile body feathers are of poor quality and, for example, to survive a harsh winter, it is certainly necessary to replace them, the flight-feathers, although of lower quality, are still usable and the animal can survive with them to the next year. A special case is also the situation when during the life of an individual some sign in the plumage enlarges, or changes the saturation of its colouration (e.g. yellow colour in male Yellowhammers, Emberiza citrinella). Even here, we could talk about DPM, however the situation is complicated by the fact that the variability in these traits is huge and usually not easily used as an indicator of age, like in the clearly separated categories of brown × red.

In conclusion, a bit of speculation on my part. When I look at the Black Redstart itself and its division into the form of cairii and paradoxus, I find out that even here the boundary between the two forms is not as sharp as is usually presented. After all, it doesn't surprise me. The testosterone level, which determines the form to which the redstart moults, also does not have only two different levels, but it is a continuum, so it is possible that the amount of black ("adult") feathers is proportional to the total testosterone level. Just take a good look at these redstarts, sometimes. On many males in the form cairii, i.e. with the illusive female appearance, you will find some dark grey or black feather that match the male's plumage. Some males in paradoxus form are almost perfect "males", while others are less prominent. After all, see for yourself in the picture below.

But what do I actually know?

A view of various male redstarts in their first year of life. In the top row, two individuals that one would determine at first sight as the cairii form, in the bottom row, two representatives of the paradoxus form. But is it really so? Isn't it rather a smooth transition?

Top left: Some cairii redstarts actually look like females. However, some of them grow a few feathers, typically grey as in adult males. Here, for example, some coverts or black feathers on the cheeks (don't be fooled, this is an animal in the autumn, even in adult males the black feathers are somewhat obscured with light edges; CZEP20-392). Top right: The same case as the previous one, here, in addition, the individual also moulted some tertials, which in adult males co-form a typical white field in the wing (CZEP21-136). Bottom left: Typical paradoxus (it is again an animal in autumn, bright colours are covered by light brown edges to the feathers). An almost exemplary appearance of an adult male. On closer inspection, however, we can see juvenile (brown) flight-feathers, including tertials and some coverts = a clear sign of the animal in its first year of life (CZEP17-441). Bottom right: Another case of the typical paradoxus form, this time photographed in the spring, when the pale edges of feathers are almost wiped off. The appearance of the adult male is almost perfect (again we can see juvenile flight-feathers, including tertials, which do not form a white field in the wing; CZEP20-136).

Summary

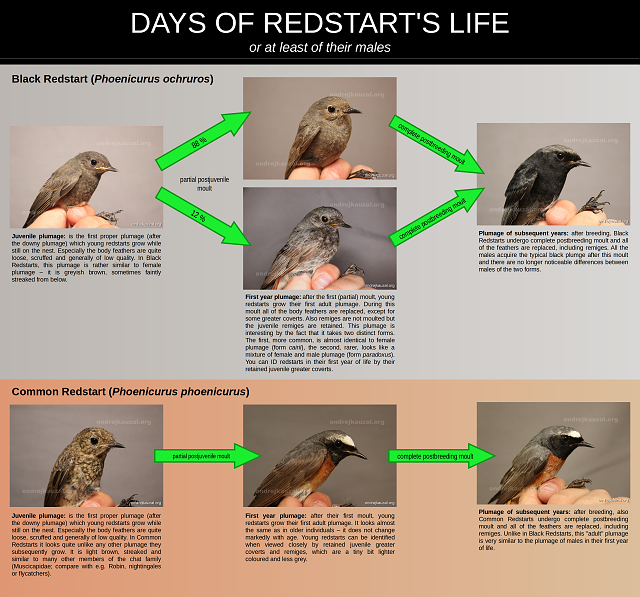

It is said that one picture is worth a thousand words, and with the next picture I tried to summarize how the Black Redstart plumage changes over time. As an example of a species that does not show DPM, I chose its relative Common Redstart.

Examples of ageing redstarts

In the following photos you can see DPM in practice. These are the photos of a male redstart in the first and next years of life. Because proof instead of promises, right?

So time went by with one redstart from our little garden. On the left is the individual in the first year of its life in a "female" plumage (cairii form, although with white edges of tertials, see above), in the middle is already a fully coloured bird in the second year of life and on the right it is in the third year when the plumage no longer changes dramatically (in the gallery: CZEP19-150, CZEP20-036 & CZEP21-064).

Another case documented by me of the process of ageing of one male of the form cairii. On the left is an individual in its first year of life in almost perfect female plumage, on the right you can see a fully developped plumage acquired the next year. (Birds in gallery:CZEP21-139 & CZEP22-101).

Photos by Filip Petřík of one of his RAS[5] redstarts photographed in two consecutive years. (Photos courtesy of Filip Petřík.)

Several cases of redstart transitions documented by Filip Petřík on avif (czech avian faunistic database):

- cairii form: https://birds.cz/avif/obsdetail.php?obs_id=9898499

- paradoxus form: https://birds.cz/avif/obsdetail.php?obs_id=8603576

- paradoxus form: https://birds.cz/avif/obsdetail.php?obs_id=9756170

You can find more and more photographs of redstarts of various ages here in the gallery , photos of one-year-old males always include a description of whether it is a form cairii or paradoxus. Although when I look at the photos for the second time, maybe I would change some captions…

I would like to thank my wife who translated most of this blogpost to English. Many thanks goes also to Anna Lučanová for the opening photo. It captures an amazing ringing experience, when they managed to trap three male redstarts at once - from the left a young male of the cairii form, an old male, and a young male of the paradoxus form, respectively. It happens just once in a lifetime! I would also like to thank Filip Petřík for other photographs of redstarts and valuable suggestions during writing this article.

References and further reading:

All links open in new tab/window.

A paper about testosterone and its effect on delayed plumage maturation in Black Redstart: Schwarzová, L., Fuchs, R. & Frynta, D. (2010) Delayed Plumage Maturation Correlates with Testosterone Levels in Black Redstart Phoenicurus ochruros Males. Acta Ornithologica 45: 91–97, doi: 10.3161/000164510X516146 (unfortunatelly without free PDF).

In their original habitat – mountain open habitats and villages – young redstarts were displaced by older males into worse territories. Which is probably not the case in modern towns. At least according to this paper: Schwarzová, L. & Exnerová, A. (2004) Territory size and habitat selection in subadult and adult males of Black Redstart (Phoenicurus ochruros) in an urban environment. Ornis Fennica 81: 33–39. [PDF, 663 kB]

Two papers about delayed plumage maturation in birds in general (contains list of species and summarizes hypotheses why this phenomenon evolved):

Cucco, M. & Malacarne, G. (2000) Delayed maturation in passerine birds: an examination of plumage effects and some indications of a related effect in song. Ethology Ecology & Evolution 12: 291–308. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2000.9522802; [PDF, 2.67 MB].

Hawkins, G.L., Hill, G.E. & Mercadante, A. (2012) Delayed plumage maturation and delayed reproductive investment in birds. Biological Reviews 87: 257–274, doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2011.00193.x; [PDF, 2.05 MB].

And what are the books where you could read about the delayed plumage maturation in Black Redstart? Well, for example in these:

- Svensson, L., Mullarney, K. & Zetterström, D. (2010) Collins Bird Guide

- Vinicombe, K., Harris, A. & Tucker L. (2014) The Helm Guide to Bird Identification

- Shirihai, H. & Svensson, L. (2018) Handbook of Western Palearctic Birds: Passerines

- Clement, P. & Rose, C. (2015) Robins and Chats

- Svensson, L. (1992) Identification Guide to European Passerines

- Jenni, L. & Winkler, R. (2020) Moult and Ageing of European Passerines

- Svensson, L. (1992) Identification Guide to European Passerines

- Cramp, S. (1988) The Birds of the Western Palearctic, Volume 5: Tyrant Flycatchers to Thrushes

And very probably in many more…

[1] Unless we have very good photographs or we have the opportunity to see the bird in hand.

[2] But, but, but, that is not possible, in our garden there is always a pair of female looking redstarts and they are there everytime and everytime in the same place and! I hear all the time, or read on social networks, as an argument why this is actually not true. It would be really interesting if it wouldn't and it would be worth of a mention in some scientific journal, at least. Even though some authors speculate that some males look like female also in consecutive years, truth is, no such case was documented until now. Much simpler explanation is the mere fact that the mortality of temperate zone passerines is huge. Much bigger than many of us are willing to acknowledge. It is very probable, that all those beautifull birdies returnig each year to our garden to nest in our nestboxes, to sing from the same perch, to batch in the same bird batch, are different animal every year. It may seem cruel to us, but truth is, the birds are set this way. That is how they live: very fast. But that is a topic for another blogpost. The fact is, that if you were to trap such male redstart, mark it with ornithological ring, you would find out, it returned next year only to became whole black, maybe in the next garden, and its place was taken by another brown male. And if not, please publish it somewhere! :)

[3] Which is typical for most finches, thrushes, Muscicapids, dippers or tits and chickadees. In other families, the situation is much more difficult, which would require to write a whole blogpost. Or a book. Like this one: Moult and Ageing of European Passerines .

[4] Young males of Collared Flycatchers arrive to breeding grounds a bit later than older ones and therefore establish territories in place where no older male nests. Females presumably choose mate based on its territory quality but such a simple yet apparent presence of juvenile feathers might serve as a clue, too. The literature does not give much information and if so, it is quite contradictory. So there is still place for some research!

[5] Project RAS (Retrapping Adults for Survival) is one of the long term ringing projects in many European countries which aims to estimate the survival rate for focal species with the use of retrapping the same individuals year after year. More info can be found here: BTO: About RAS .